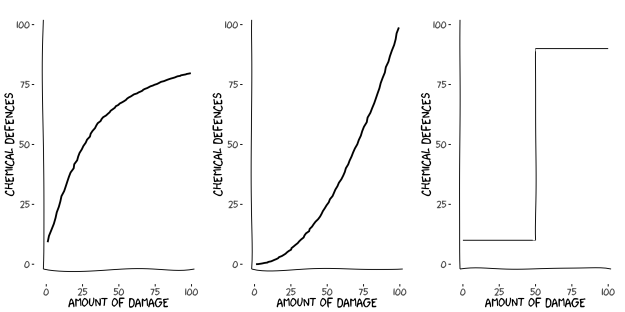

As usual, there’s an XKCD comic for everything.

Not long after I received my first permanent academic contract I attended a conference and went out drinking after the sessions. By the end of the evening I found myself amongst a large group of people around my own age, mainly post-docs and PhD students. Conversation turned to careers and it so happened that I was the only one with a secure position, which prompted an immediate question. What was the secret? Everyone was feverishly after the same thing, and here was someone in the room who knew the trick.

My answer, ‘luck’, went down like a glass of cold sick. It was honest but unpopular. I now regret saying it, and realise that I should have added ‘privilege’. At the time I hadn’t appreciated the extent to which privilege played a part in the relatively smooth passage of my career*. It didn’t seem that way to me, but in retrospect I certainly had it easier than most. The truth, however, is that ‘luck’ is often the secret, insofar as it’s the element no-one wants to talk about. All the other things, the ones we can either control or are imposed upon us, are obvious. I had none of the magic bullets: no Nature paper or prestigious research fellowship**. Objectively there was nothing on my CV that set me apart from most other post-docs on the job circuit. It certainly felt a lot like luck to me.

Why don’t people like to hear this? Accepting the importance of luck downplays the extent to which anyone has agency in their professional lives. We like to hear that working hard and chasing our dreams brings success in the end. I think for the most part that it’s true, and almost everyone who manages to get into the ivory tower will tell you that backstory. But it’s akin to hearing an Olympic gold medalist tell you that their secret is dedication and never giving up. As if all the people that didn’t come first just weren’t dreaming hard enough.

Telling people to keep plugging away until they get their break also assumes that there are no costs to them doing so. It’s the mindset that leads to the eternal post-doc, a restless soul traveling from university to university, country to country, for the chance of another year or two of funding, then having to pack up their things and move on once again. While still young and relatively carefree, that can be fun for some. When you’re 40 and want to get married, buy a house, have children or care for your parents, it becomes impossible. I never had to go through that and I’m extremely grateful for it.

Declaring the importance of luck and privilege also somehow diminishes the achievement of those who have made it, and therefore provokes hostility from those who are already through the door. It’s not the story we like to tell ourselves, and it’s certainly not one we like other people to tell about us.

So let me lay my own cards on the table. I believe that I deserve to have a permanent academic job***. I worked hard to get here, and I’m pretty good at it. But I can also say without any equivocation that I’ve known people who worked much harder than me and were demonstrably smarter than me but who didn’t manage to capture one. I’m comfortable admitting that although I surpassed the minimum expectation, if it were a true meritocracy then the outcome would have been different.

My first job came about because I was in the right place at the right time. I had hung around long enough in a university department to pick up the necessary ticks on my CV, despite substantial periods of that being spent on unemployment benefit. Small bits of consultancy through personal connections and a peppercorn rent from a friend made a big difference. I had the privilege of being in a position to loiter long enough for a job to come up, and the good fortune to find one that fit. Lots of others wouldn’t have had the luxury of doing so, and had it taken another six months, I wonder whether I would have been hunting for another career as well.

Does any of this change the advice given to an eager young academic? No. You still need to publish papers, get some teaching experience, win some competitive grant income, take on some service roles, promote yourself and your work as widely as possible. The formula remains exactly the same. It’s not easy, and it’s got even harder over the last 15 years. Good luck. And if you don’t have luck, make sure that you have a Plan B in your back pocket.

Any change needs to come from the academy itself. Its us who have the problem and it’s our responsibility to fix it****. There’s no way to entirely remove luck from the hiring equation (think of it as a stochastic model term) but we can influence the other parameters. I was wrong to think that privilege wasn’t part of the equation that got me here, but I can try to minimise its distorting effects in future.

* I have the ‘full house’ of privileges, being a white, male, heterosexual, tall, healthy, able-bodied, native English-speaking, middle class… did I miss anything out? Don’t bother talking to me about my struggle because I didn’t have one.

** The one thing jobs, Nature papers and grants all have in common is that your probability of getting one increases with the number of times you try. It’s not entirely a lottery but there is a cost to every attempt and some can afford more of them. And I still don’t have a Nature paper.

*** There are almost certainly people who will disagree with this, but let them.

**** As pointed out in this post, however, our survivorship bias can prevent us from recognising that those following us are facing very different challenges to the ones we went through.

Postscript: I already had this post lined up to publish when an excellent and complementary thread appeared on Twitter.